You can listen to the audio narration of this article here.

Introduction:

When you think of Jesus Christ, the apostle Peter, or an angel, what do they look like? While we can’t know for certain what any of these figures look like, you probably thought of an artistic depiction of these figures, perhaps a painting or stained glass window. Art is a good gift from God, but a certain abuse of this gift, namely icons, has permeated many church bodies for millennia. Many in Eastern Orthodoxy and Catholicism use images1 in worship, venerating and praying to the figures they represent. As mentioned in our previous article, Calvinists have historically opposed the use of images. But who is really more consistent with the practice and views of the early church, Reformed Christians, or the Catholic church they sought to reform?

The History of Christian Icons:

Drawings of biblical figures have been discovered dating back as early as the 3rd century. Currently, the recently excavated house church in Dura-Europos,2 Syria is thought to contain the earliest drawings of Jesus. He was depicted as the “Good Shepherd” (a very popular depiction) and shown in another drawing healing the paralytic. However, it wasn’t till the Edict of Milan in 313 (which legalized Christianity) that icons became commonplace and the objects of veneration. The reasons for this are up for historical debate. Was it due to Christians finally being free to express the artistic influences which had been there all along (as a pro-icon historian might argue), or was it due to an influx of pagans bringing their artistic influences into the church (as an anti-icon historian might argue)? It’s undeniable that many in the early church opposed icons, despite what icon advocates would have you believe.

An excellent example is the influential father Clement of Alexandria (150-215), who said (Paedogogus, Book 3, Chapter 11):

And let our seals be either a dove, or a fish, or a ship scudding before the wind, or a musical lyre, which Polycrates used, or a ship’s anchor, which Seleucus got engraved as a device; and if there be one fishing, he will remember the apostle, and the children drawn out of the water. For we are not to delineate the faces of idols, we who are prohibited to cleave to them; nor a sword, nor a bow, following as we do, peace; nor drinking-cups, being temperate.

Nor was this the opinion of some isolated writer; the Council of Elvira (held circa 306 in Spain) said, in Canon 36:

It has seemed good that images should not be in churches so that what is venerated and worshiped not be painted on the walls.

Other instances like these could be adduced, showing that the idea of creating these images was not a universal Christian concept. It’s our contention that the pagan origin of many of the images in the church is undeniable. There is a striking resemblance between much pagan and Christian art of the era.

Editor’s Note: Please be aware there is some immodesty in the following images. They are presented only to illustrate the historical claims made.

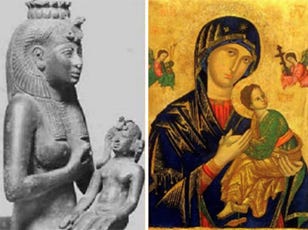

Left: Egyptian goddess Isis feeding her son, Horus; Right: Mary, mother of Jesus, holding her son.

Top: Jesus Christ Pantocrator; Bottom: Serapis, god of the Sun (shared by Greeks and Egyptians).

Top: The apostle Peter; Bottom: Zeus, supreme god in Greek and Roman mythology.

8th Century to Present:

After the early church period, icons became more prevalent, especially during the centuries leading up to the Great Schism. In the 8th and 9th centuries the Iconoclastic Controversy developed, a debate over the use of icons. Leo III of the Byzantine Empire (the eastern portion of the former Roman Empire) officially prohibited icons, and his successor, Constantine V, followed in his footsteps by actively persecuting icon venerators. However this iconoclastic period was short-lived as Irene, the new Byzantine empress, restored the use of icons in 787. This began the second iconoclastic period wherein those who opposed icons (the iconoclasts) struggled to regain power in order to ban icons yet again. While they were able to do so under Leo V, they eventually lost power again in 843 under Theodora. In fact, this final act of icon restoration is celebrated by Eastern Orthodox churches in the “Feast of Orthodoxy.”

Our historical summary began with the New Testament church, but what about the Old Testament church? Of course, there were numerous periods of apostasy where God’s people used images, most notably the instance of the golden calf, but for thousands of years before Christ, Jews generally held that using images in worship was wrong. Even to this day, Jews do not use images in worship. The reason for this unanimity of God’s people was the clarity of God’s word.

Why Images in Worship Are Prohibited:

The second commandment very straightforwardly addresses the issue (Exodus 20:4-6):

You shall not make for yourself a carved image, or any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth. You shall not bow down to them or serve them, for I the LORD your God am a jealous God….

Moses explains the reasoning for this commandment in Deuteronomy 4:15-20:

Since you saw no form on the day that the LORD spoke to you at Horeb out of the midst of the fire, beware lest you act corruptly by making a carved image for yourselves…. But the LORD has taken you and brought you out of the iron furnace, out of Egypt, to be a people of his own inheritance, as you are this day.

Images are prohibited because God reveals himself not through visible “forms” but through speaking and acting.

Ever since images came into the churches, people have attempted to muddy this clear command. The primary argument, especially of Roman Catholics, is that the commandment only prohibits worshipping images and that they only venerate images. They will further point to the creation of the bronze serpent (Numbers 21) and the cherubim on the mercy seat (Exodus 25:17-22) as proving the point: God allowed the creation of images so long as they were not worshipped. However, both the argument and the supposed evidence fail. First, the commandment makes no distinction between worship and veneration; rather, it prohibits even external acts which could look like worship: “You shall not bow down to them or serve them.” Second, the bronze serpent was not a part of worship, and when the Israelites started using it in worship, King Hezekiah destroyed it (2 Kings 18:4). And the cherubim were not used in public worship either. The high priest alone would see them once annually on the Day of Atonement when he entered the Holy of Holies (Leviticus 16). Furthermore, even if we grant the Roman Catholic argument for a minute, that God did in fact make two exceptions to the command, God making his own exceptions to his law in no way permits us to carve out our own exceptions.

Another argument (probably originating with John of Damascus) is that the incarnation inaugurated a “new economy” of images: Because Christ is the “image” of God, we are now permitted to make images of Christ the man. However, it is impossible to separate the deity of Christ from his humanity (to do so is the Nestorian heresy), and so it is impossible to image Christ without imaging deity. Therefore, this argument fails as well.

Conclusion:

The thesis of the Reformation was that the church had forgotten the faithfulness of her early days, a faithfulness she desperately needed to recover. Part of this faithfulness was the rejection of images and icons dictated by God in the second commandment. Thankfully, the Reformers had a pattern of obedience to follow in the early church and the Old Covenant church, which also generally eschewed images. May we continue to follow their obedience. God bless.

We’re using the terms “icon” and “image” interchangeably.