Listen to the audio narration of this article here.

Introduction:

Few topics engender as much outrage and hysteria as slavery, and yet on few topics is there such endemic ignorance, both on what the Bible says and on the true historical situation. Our culture takes it as a given that all slavery is universally evil. In fact, one is far more likely to hear slavery mentioned as an objection to Christianity, especially by young people, than more standard arguments (such as evolution or the historicity of Scripture). Consequently, there is tremendous pressure on Christians to “find” the same view presented in Scripture. However, the Bible has a way of not fitting into preconceived notions, especially our modern, liberal notions. This means the biblical view of slavery will likely cut against the grain. For Christians to handle such a thorny, controversial topic, we need an absolute, steely confidence in the word of God, and to believe every part of it, without equivocation or embarrassment. This is easier said than done, but if you have that, we are ready to commence.

The Christian View of Property Rights:

At its most basic level, the question of slavery is a question of property rights: Is it ethically permissible to own another person? If not, why not, and if so, are there any other ethical restrictions? The foundation of the Christian philosophy of property rights is that “God created the heavens and the earth,” (Gen. 1:1) and thus, “The earth is the Lord’s and the fullness thereof, the world and those who dwell therein,” (Ps. 24:1). God has given ownership, or dominion, over the earth to man (Gen. 1:26), and he has done so through covenant. But this bequeathal is not absolute or unconditional; God’s dominion covenant comes with sanctions, which are collectively called “God’s law.” And so, under God’s creation covenant, our property rights, even over ourselves, are never absolute but rather subject to the conditions – the laws – imposed by God. These are written for us primarily in the Pentateuch, though of course the prophets and apostles provide ample commentary, expansion, application, and insight.

Slavery and God’s Law:

So the question really becomes, “Does God’s law permit slavery (the ownership of other people)?” And the answer is a clear, resounding yes. God explicitly permits it in the Pentateuch, and the prophets, Jesus, and his apostles all uphold it as legitimate. In fact, even before the law, we see Abraham keeping slaves, and God does not condemn this. Rather, God goes further in Genesis 17:12-13:

He who is eight days old among you shall be circumcised. Every male throughout your generations, whether born in your house or bought with your money from any foreigner who is not of your offspring, both he who is born in your house and he who is bought with your money, shall surely be circumcised. So shall my covenant be in your flesh an everlasting covenant.

God treats slavery not as a mere economic arrangement but as a profoundly deep bond, comparable to the bond one has with one’s own children. Far from being a means of excluding or humiliating, slavery is here treated as a means of including and honoring. God’s view, radically different than our own, is what underlies the laws he gives about slaves.

These laws laying out the framework of biblical slavery are primarily in Exodus 21 and several supporting passages. Hebrew slaves, unlike foreign slaves, who could be held in perpetuity (Lev. 25:44-46), were to be offered their freedom on the seventh year. And, if they chose to leave, they were to be given means of supporting themselves (Deut. 15:12-18). However, they could choose to remain slaves permanently (Ex. 21:5-6):

But if the slave plainly says, “I love my master, my wife, and my children; I will not go out free,” then his master shall bring him to God, and he shall bring him to the door or the doorpost. And his master shall bore his ear through with an awl, and he shall be his slave forever.

The very idea that a slave would love his master and desire to remain his property indefinitely is certainly a novel one to us moderns, but it’s basic to the biblical view.

Beyond the seven-year restriction, God also prohibited slaves from being abused; masters who killed their slaves, even accidentally, were subject to the death penalty (v. 20-21) and inflicting permanent injury meant the slave went free. Deuteronomy 23:15-16 prescribes that runaway slaves are not to be returned to their masters. Since slaves were given a generous parting gift, the only reasonable situation in which a slave would runaway is if he served an abusive master. Most importantly, a person could not be kidnapped and sold as a slave – this was also a capital offense (Ex. 21:16).

The remainder of the Old Testament rests on these assumptions, and we see slavery portrayed as a legitimate practice (when in the bounds of God’s law). Perhaps most striking is Job, a “blameless and upright” man, who kept slaves (Job 1), and when defending himself, Job mentions he treated his slaves fairly (v. 31:13). Similarly, God argues through the prophet Malachi that he deserves the respect a slave has towards his master. It would seem very odd indeed for God to point to an immoral activity as a picture of moral virtue.

Slavery and the New Testament:

Many modern Christians, troubled by the Old Testament’s unblushing endorsement of slavery, attempt to explain it away, mumbling some variation of, “Well, that was the Old Testament.” In response to this common trope, Gary North developed the quip, “The Old Testament is not ‘The Word of God Emeritus.’” That any professed Christian would seek to undermine the authority of God’s law-word is frankly blasphemous, but moreover, it’s ironically self-defeating. The objection mistakenly portrays the Old Testament as harsh and the New Testament as more “reasonable.” But, if anything, the New Testament is more hardline on the issue of slavery. In the Old Testament, God laid out numerous provisions for the protection of slaves, but such protections did not exist in Greco-Roman law. Jesus healed the centurion’s slave without releasing him (Matt. 8:13). Paul commanded slaves to obey and labor diligently for their masters (Eph. 6:5-9; Col. 3:22-4:1), and encouraged the runaway slave Onesimus to return to his master Philemon.1 Peter even commands slaves to obey not only good but also harsh masters. In no way can the New Testament be construed as opposing slavery or differing with the Old Testament. In fact, at every point, it reaffirms the justice of the Mosaic Law.

Conclusion:

Scripture is absolutely clear on slavery and teaches one unified message across both Old and New Testaments. Its clarity, however, will not stop Christians from caving to cultural pressure. Truth be told, many people, even professed Christians, have a gut-level distaste for God’s law. Slavery is actually a mercy from God, presented as a means of supporting those who, for various reasons, cannot support themselves. Biblically, slavery, far from being a cruelty, is actually a mercy, which is polar opposite from our culture’s view. Thus we see the truth of the proverb “The mercy of the wicked is cruelty.”

Since this is such a complicated topic, Lord willing, we will be writing another two articles on slavery, the first applying this biblical framework to American slavery and making an ethical assessment, and the second explaining why slavery is an inescapable concept.

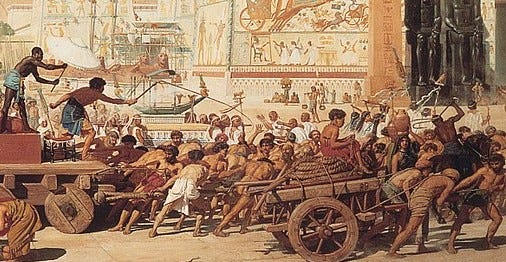

Editor’s Note: The thumbnail image is a detail of the 1867 painting “Israel in Egypt” by Edward Poynter.

For clarification, this does not conflict with the law in Deuteronomy 23 since Onesimus surely returned willingly in repentance. Furthermore, some argue Paul “freed” Onesimus on the basis of verses 15 and 16:

For this perhaps is why he was parted from you for a while, that you might have him back forever, no longer as a slave but more than a slave, as a beloved brother—especially to me, but how much more to you, both in the flesh and in the Lord.

However, since Paul has previously given commands to Christian masters and slaves, “receiving him as a beloved brother” is not equivalent to freeing him. Second, Paul’s offer to pay for any of Onesimus’ wrongs indicates he probably believed Onesimus had wronged his master. Third, Paul always goes to great lengths to make himself clear and explicitly state his intentions; if he was actually freeing Onesimus, we should expect a clear statement of such, which is in fact nowhere to be found.

Article by A.C. For more articles like this, join us on MeWe, Telegram, Gab, YouTube, or feel free to: